Verifying Distributed Protocols in Veil

In this post, we discuss how to formalise, test, and prove the correctness of a classic distributed protocol by combining model checking, automated deductive verification, and AI-powered invariant inference in Veil, a new auto-active Lean-based verifier for distributed protocols.

Introduction

A famous quote by Leslie Lamport states:

“A distributed system is one in which the failure of a computer you didn’t even know existed can render your own computer unusable.”

While implementations of distributed systems are typically very large programs of tens of thousands of lines of code, at the heart of each such system is a distributed protocol—an algorithm responsible for enabling all parts of the system to communicate with each other so that the system delivers correct results to its users. That said, even though descriptions of distributed protocols are usually one to two orders of magnitude smaller than their respective implementation, getting those protocols right is still a rather challenging endeavour, due to their inherent concurrent nature and a large number of “moving parts”, especially in the presence of possible faults.

The complicated nature of distributed protocols has made them a popular subject for formal modelling and validation using computer-assisted tools, such as TLA+, P, and Quint. TLA+, designed by Lamport himself, is perhaps the most popular such framework today. It is used widely by designers and implementers of distributed protocols in industry to quickly prototype protocol designs and validate their properties by exhaustively testing them on a fixed set of parameters—an approach known as model checking.

A significant shortcoming of all these tools when it comes to gaining trust in distributed protocol design is their rather rudimentary support for machine-checked formal proofs of distributed protocol correctness. That is, these tools are excellent at finding bugs in protocol designs, but make it challenging to prove that a distributed algorithm never violates its correctness specification.1

To address these shortcomings, we developed Veil—a “one-stop shop” framework for prototyping, model checking, and verifying distributed protocols, with ultimate correctness guarantees. Similar to our other verifier Velvet, Veil is built on top of the Lean proof assistant, as a library, so it naturally benefits from Lean’s expressive specifications, rich collection of data types and mathematical theorems, and the toolset for proof scripting and automation. Furthermore, we strove to replicate the best parts of TLA+ in Veil, namely, its ability to state protocol specifications at a high level of abstraction (i.e., without spelling out each insignificant implementation detail) combined with the ability to model-check such specifications, quickly discovering “shallow” bugs, before focusing on formal correctness proofs.

In the rest of this post, we will discuss how to encode, model check, and semi-automatically verify a classic consensus protocol in Veil. In future posts in this series, we will focus on more advanced Veil features, such as combining automated and interactive Lean proofs about distributed protocol correctness.

A Classic Example: Dolev-Strong Floodset Protocol

To showcase Veil, we will use it to model the Dolev-Strong Floodset protocol, a classic distributed algorithm allowing $N$ nodes to reach agreement, i.e., select the same value uniformly, by exchanging messages with each other. Notably, this is a fault-tolerant protocol: it allows for $t < N$ nodes to fail during the protocol’s execution—meaning that they will stop sending messages.

The Floodset protocol ensures agreement between non-faulty nodes under an assumption of synchrony, meaning that the nodes communicate in discrete, numbered rounds, and all messages sent in a given round are guaranteed to be delivered before the next round starts. This is a strong assumption, as it allows a node $n$ in the protocol to infer that, if it has not heard from a node $m$ in a certain round, that is because the node $m$ is faulty, and not because the network is slow.2

The protocol’s logic is rather simple. It starts with each node choosing a value from a certain finite set of totally ordered values (the need for ordering will become clear soon). Next, they communicate in $t + 1$ rounds. In each round, each non-faulty node broadcasts (i.e., sends to everyone in the network) all values it is aware of. Initially, this is just the value it has chosen at the start, but this set will grow as it “hears” from other nodes. After $t + 1$ rounds, each node selects the smallest value from those it is aware of, according to the ordering, and concludes that this is the value that all nodes should agree on.

Let’s try to convince ourselves that this protocol works, in the sense that after $t + 1$ rounds of communication, despite the possible failures, all nodes that survived choose the same value.

First, let us notice that if there are no failures, just one round of communication between all nodes is sufficient. Indeed, if everyone hears from everyone, every node will be aware of every value any node (including itself) has chosen by the end of this round. Given that all of them exercise the same rule of choice—just choosing the smallest value in the set—they will all choose the same result.

Things get trickier if there are failures. The problem is: a faulty node can fail in the middle of its broadcast, so some of the nodes will receive its messages, and some will not. So, by the end of the round, some of the alive nodes might be aware of different values. To make things worse, multiple nodes might fail during the same round, increasing the amount of chaos in the system even further.

So why does the protocol work at the end? Notice that to reach agreement, we only need one fault-free round during the entire execution, as by the end of this round every node will “synchronise” with each other on all the data in the system. Since we assumed up to $t$ faults and $t + 1$ rounds, even if one node fails in each round, by the pigeonhole principle there will be at least one fault-free round, in which everyone will get everyone’s data. And even if some nodes fail after that, it will not change this knowledge (although it’s possible that alive nodes will agree on a value proposed by some node that has failed at some point).

Let us now go ahead and encode the protocol in Veil, proving that this intuition is, in fact, true.

Encoding Floodset Protocol in Veil

Disclaimer: Veil is a research prototype and is currently under active development by VERSE lab. Its performance as an automated verifier might vary on different case studies, and some of its UI aspects (e.g., syntactic error highlighting) will be improved in the future. Please, get in touch with us if you are planning to use it, and feel free to submit bug reports to the GitHub repository.

The protocol model accompanying the rest of this post can be found in this file. If you don’t want to compile Veil, you can try its web version (although be prepared that it’s not very fast).

Representing State Space

To encode a distributed protocol in Veil, we start by creating a new Lean

file (let’s call it FloodSet.lean) with the command that imports Veil as a

Lean library and makes a new Veil module, where we will put all our definitions

and properties:

import Veil

veil module FloodSet

-- The protocol definition and its properties will be here

end FloodSet

Next, we will define the state of our protocol. Unlike actual implementations of distributed systems, where each node runs its own code, formal descriptions of distributed protocols typically model the system holistically: the state captures the information held by all nodes at once, and transitions describe how a single node’s action updates this global state. This style greatly simplifies formal encoding of the protocol’s logic while retaining all its characteristic intricacies. Readers with experience in TLA+ or Quint will find Veil’s encoding style very familiar.

We first declare the types of the node identities and the values they exchange:

-- Abstract types for nodes and values

type node

type value

-- Values must be totally ordered (for picking the minimum)

instantiate val_ord : TotalOrder value

open TotalOrder

At this point, it is not important what the elements of node and value are

exactly: they can be integer numbers, strings, etc., but knowing their structure

is not necessary for modelling the protocol’s logic (and also, surprisingly,

makes it easier to verify it), so we deliberately omit these details. The only

thing that we need to postulate now is that elements of value are totally

ordered, which is what is done by the line instantiate val_ord : TotalOrder

value.3

Next, we proceed to the components of the state space of the protocol, which one can think of as a record with several fields:

immutable individual t : Nat

individual round : Nat

individual crashCount : Nat

function initialValue : node → value

relation seen : node → value → Bool

relation decision : node → value → Bool

relation alive : node → Bool

relation crashedInThisRound : node → Bool

#gen_state

Scalar state components (i.e., non-functions) in Veil are declared using the

individual keyword.4 Components that remain constant throughout the

entire protocol’s execution, such as the maximal allowed number of faulty nodes

t, can be marked as immutable. This is not strictly necessary, but it

improves the performance of model checking and helps with simplifying the proofs

by signalling Veil that it does not need to keep track of changes in those

values. Since both the round number (round) and the actual number of crashed

nodes (crashCount) will increase during the system’s execution, those are not

marked as immutable.

Non-scalar components in Veil model many-to-one and many-to-many relations

between values in the system. For instance, the initialValue function will

represent the values chosen by nodes at the beginning of the protocol. The

binary relation seen captures the values each node is aware of at any point.

That is, seen n v = true means that the specific node n is aware of the

value v. In a similar vein, decision encodes which nodes have decided on

which values. Even though each node will eventually select at most one value, it

is much more convenient to “over-provision” the definition for a possibility of

a node to choose multiple values—don’t worry, we will later verify that this

never happens. Finally, the two unary relations alive and crashedInThisRound

capture the nodes alive at any moment of the protocol’s execution and the nodes

that have crashed since the start of the current round, respectively.

Given these declarations, Veil command #gen_state produces an internal

representation of the protocol’s state, so we can use it to describe how

exactly the algorithm works.

Initial States

Now comes the most interesting part: modelling the protocol’s logic, i.e., describing how exactly it starts and runs. Let’s start by describing the set of possible initial states of the protocol:

-- Initial state: each node has exactly one proposal value

after_init {

initialValue := *

seen N V := initialValue N == V

alive N := true

decision N V := false

round := 0

crashCount := 0

crashedInThisRound N := false

}

There is quite a bit to unfold in this definition.

Let us start with the line initialValue := *. Remember that initialValue is

a function of type node → value defining which value each node chooses at the

beginning. It is not important what exact value each node chooses, and, in

fact, we are interested in checking all possible combinations. This Veil syntax

allows us to achieve exactly this: picking a definition of initialValue

arbitrarily. The power of this feature will become clearer once we start

model-checking (i.e., exhaustively testing) and verifying the correctness of the

protocol. In the former case, it will ensure that we run the check for every

possible definition of initialValue. In the latter, it will allow us to

prove that the protocol’s correctness holds regardless of which definition of

initialValue it starts with.

The second line seen N V := initialValue N == V shows another important

feature of Veil, inspired by the Ivy

verifier—so-called iterated assignments. Whenever we use a capitalised

variable, e.g., N in the code of Veil actions (and later, protocol

properties), it should be read as “for any N in the respective set”. More

specifically, here we define the Boolean value of seen N V for any pair (N,

V) as the value of the expression initialValue N == V. In other words, if,

for a given N and V, initialValue N returns V, then seen N V is set to

true, otherwise it’s set to false. This syntax might be a bit weird when you

see it for the first time, but soon it becomes very natural, and you might appreciate

its conciseness and elegance.

With the syntax explained, the rest of the definition should be clear: every

node N is alive at the start of the execution, and has not decided on any

value (decision N V := false). We start from the round 0, with 0 crashed nodes

and no node crashed in the initial round.

Protocol Actions

To model an execution of distributed protocols, we must embrace their non-deterministic nature: in essence, at any point, one of many things can happen in the system, and we do not always have control over the exact order of these events. That said, we should also be able to express which event might or might not happen given the state of the system so far. Let us see how to accommodate these requirements and express distributed events using the mechanism of Veil actions.

For example, this is an action that describes an event of a node failing:

-- Crash one alive node (can happen multiple times per round, up to t total)

action crash (n : node) {

require round < t + 1

require crashCount < t

require alive n

alive n := false

crashedInThisRound n := true

crashCount := crashCount + 1

}

This definition states that an action crash can be executed at any point for

any node n given that the following side conditions are satisfied:

- The current value of

roundis less thant + 1 - The value of

crashCountis less thant - The node

nisalive

The combination of these requirements will prevent us from crashing more than

t nodes, doing so after the end of the protocol’s main “run”, and crashing the

nodes that have already failed.

What follows is the “operational” logic of the action. It first marks the node

n as failed (alive n := false). Then, it records the fact that n has

crashed in the currently ongoing round (crashedInThisRound n := true). Finally,

it increases the total counter of crashed nodes.

It is important to note that, despite the concurrent nature of distributed protocol executions in Veil, there are no “data races” between actions: multiple actions are always assumed to be executed atomically, one after another. What remains non-deterministic is the order in which they might be scheduled for execution. Indeed, Veil’s machinery for model checking and verification will account for that, to make sure that every such execution is accounted for at the end.

Next, let us describe the most important part of the Floodset algorithm:

synchronously advancing rounds, making nodes exchange data with each other. This

is done by the advanceRound action:

action advanceRound {

require round < t + 1

let deadToAliveDelivery : node → node → Bool :| true

seen N V := seen N V ||

alive N &&

decide ((∃ m, alive m ∧ seen m V) ∨

(∃ d, crashedInThisRound d ∧ deadToAliveDelivery d N ∧ seen d V))

crashedInThisRound N := false

round := round + 1

}

The most interesting part of the advanceRound action is how it propagates the

information about seen values between nodes by updating the seen relation.

Notice that, due to our synchrony assumption, there is no need to model the

message-passing explicitly, since the delays between sending and receiving

messages are not observable in our system: effectively, every message reaches

its destination within a single round, or is lost forever. That’s why we can

update seen N V for any node N and value V in a single iterated

assignment. The assignment constructs the new relation by taking the union of

the old one (via Boolean disjunction ||) with the newly received data. This

data is only relevant for nodes that are still alive (hence the conjunction with

alive N). A new value V may come either from the seen-set of some

presently alive node m (∃ m, alive m ∧ seen m V) or from the seen-set of

some recently crashed node d.

The latter aspect of the model deserves a small discussion. What we want to

express here is that some of the alive nodes might hear from some of the

failed nodes. We don’t want to tell for which pairs of failed/alive nodes this

is the case, hence we model this by non-deterministically choosing this

many-to-many relation as a function deadToAliveDelivery:

let deadToAliveDelivery : node → node → Bool :| true

This syntax effectively tells Veil to assign to deadToAliveDelivery some random

function of type node → node → Bool, such that it satisfies predicate true

(in other words, the choice of the function is unrestricted).5 Getting

back to the last line of the iterated assignment to seen in advanceRound, we

can see that, for a fixed choice of deadToAliveDelivery, only the nodes N

such that deadToAliveDelivery d N == true for some node d that failed in this

round will guarantee the delivery of a value V from d’s seen-set to N.

The call to Lean’s decide function is a slightly annoying necessity, needed to

convert from Lean native propositions (of type Prop) to Booleans, imposed by

the presence of the existentially-quantified statements such as (∃ m, alive m ∧

seen m V).

The remainder of the advanceRound action “resets” crashedInThisRound to

discard the nodes crashed in this round from affecting the outcome of the next

round (any node that will be crashed via the crash action from this point on

might only affect the outcome of the next round). Finally, it advances the

round number.

The last action of the protocol is nodeDecide, which allows any alive node to

select the value of the consensus in the round t + 1:

action nodeDecide (n : node) {

require round = t + 1

require alive n

let v :| seen n v

assume ∀ w, seen n w → le v w

decision n V := V == v

}

Once again, we use the constrained non-deterministic choice operator to pick the

value v such that it’s in the seen-set for the node n. We additionally

constrain it, via Veil’s assume statement, to be the smallest possible value

amongst those seen by n. At the end, we set the decision of n to only

contain the chosen value v that (a) it has seen and (b) is the smallest amongst

all values seen by n.

Specifying Protocol Safety Properties

Now, with the definition of the protocol at hand, let us try to ensure that it indeed does what it’s supposed to do: makes all alive nodes uniformly decide on exactly one of their initial values. In Veil, we can encode this specification using the following two statements:

safety [agreement]

∀ n1 n2 v1 v2, decision n1 v1 ∧ decision n2 v2 → v1 = v2

safety [validity]

∀ n v, decision n v → (∃ m, initialValue m = v)

The keyword safety indicates a property of a protocol that must not be

violated by any state that is (a) either amongst its initial states (defined via

after_init) or (b) reachable from an initial state by executing a

sequence of one or more actions: crash, advanceRound, or nodeDecide. The

names of properties are optional and can be omitted.

Here, agreement states that any two values v1 and v2 that some nodes n1

and n2 decide upon are, in fact, the same. Notice that this property also

ensures that each node only decides on the same value (in this case n1 = n2).

Here, we are not concerned with whether the node is alive or crashed (in fact, a

crashed node will never get to make a decision, as per the premise of the

nodeDecide action). The second property, validity, states that any decided value

originates from some node’s initial value choice.

Catching Bugs in Specification with Model Checking

To check that both agreement and validity do indeed hold true for our

encoding of Floodset, we are going to use Lace, a model checker of Veil.

Lace works similarly to TLC, the model checker for TLA+. Given concrete finite

sets representing core data types of the protocol, it simply runs the model,

starting by enumerating all of its initial states, and then by applying to the

already reached states any enabled actions (i.e., actions whose

require-statements are satisfied by those states), until this process exhausts

the entire state space of the protocol, or is interrupted.

We can run Lace directly from a Lean file with the following command:

#model_check { node := Fin 3, value := Fin 2 } { t := 1 }

Fin n is Lean’s native data type that represents the finite collection

containing {0, ..., n - 1}. We use it to specify that the set of nodes is the

finite set {0, 1, 2}, and the set of values to choose from is {0, 1}. We

also allow for at most one crash by setting the immutable protocol parameter t

to 1. After a few seconds, the command produces the following output shown in

the Lean InfoView buffer of VSCode:

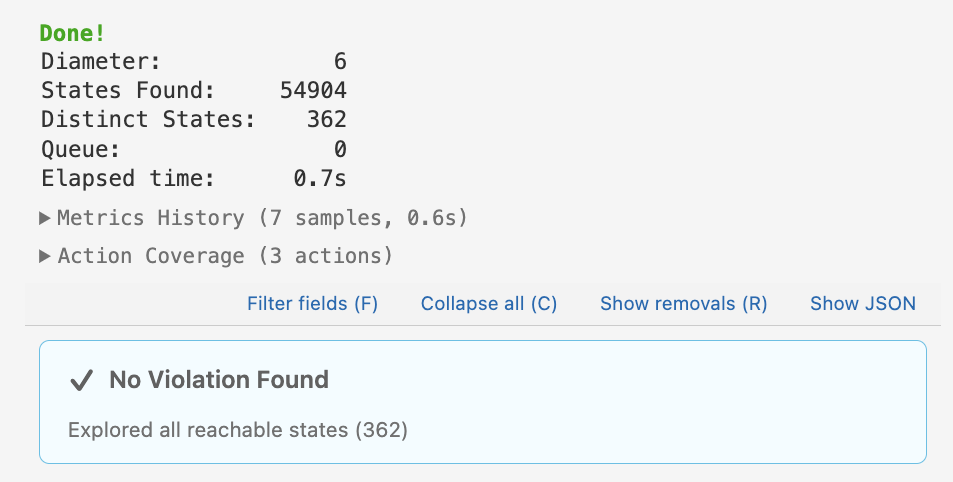

VSCode with Lean 4: testing

properties of the Veil implementation of the Floodset algorithm. The InfoView

panel on the right shows statistics for the execution.

VSCode with Lean 4: testing

properties of the Veil implementation of the Floodset algorithm. The InfoView

panel on the right shows statistics for the execution.

In particular, Lace has explored 54904 states of the protocol, of which 362 were

distinct, and the execution diameter, i.e., the maximal length of an execution

trace, was 6 actions (you can think of such a scenario as an exercise). The

large number of states is explained by the combinatorial explosion of

possible executions of the protocol: since our encoding relied on

non-deterministic choice (e.g., by setting initialValue := *), the model

checking algorithm had to enumerate all possible outcomes of such choices.

Model checking is tremendously useful for debugging the logic of the protocol

and its properties, as it can quickly discover bugs that are relatively

“shallow”—i.e., that manifest at small diameters. For instance, if we introduce a

bug by commenting out the line assume ∀ w, seen n w → le v w in the action

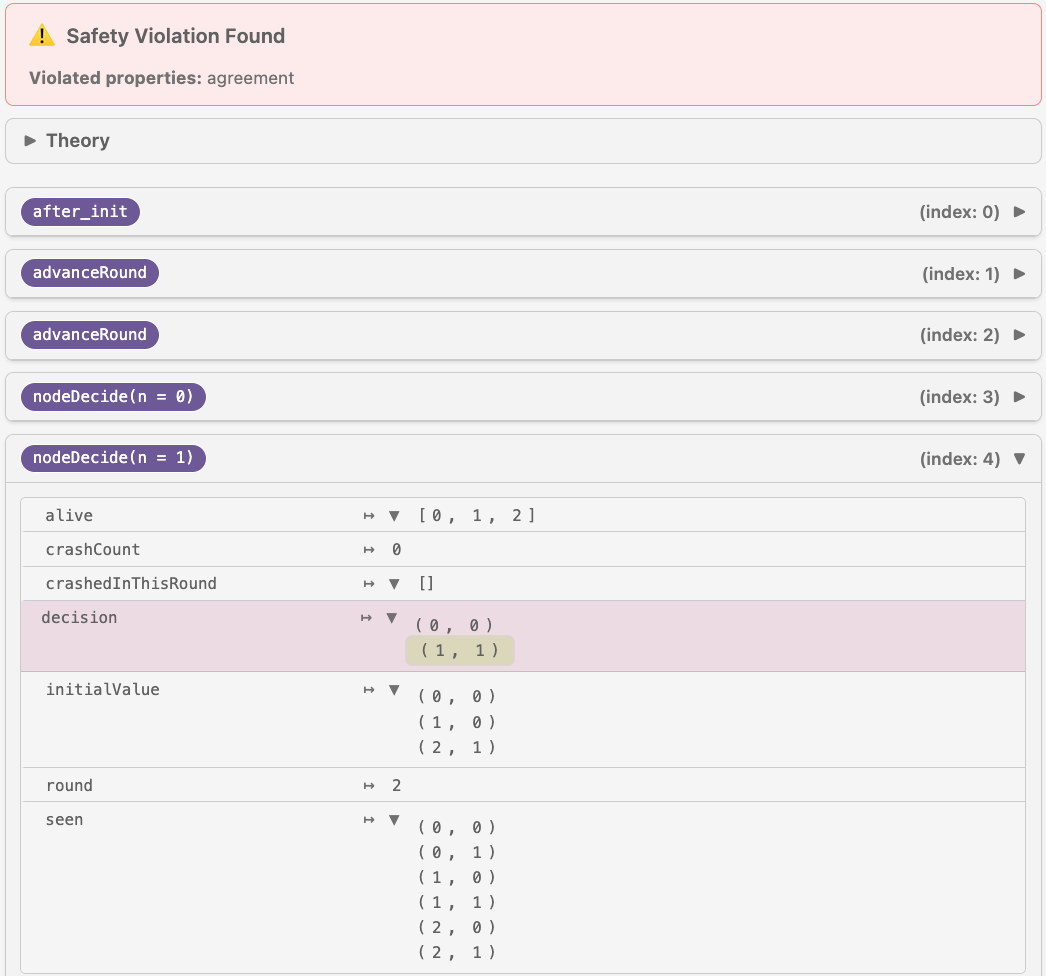

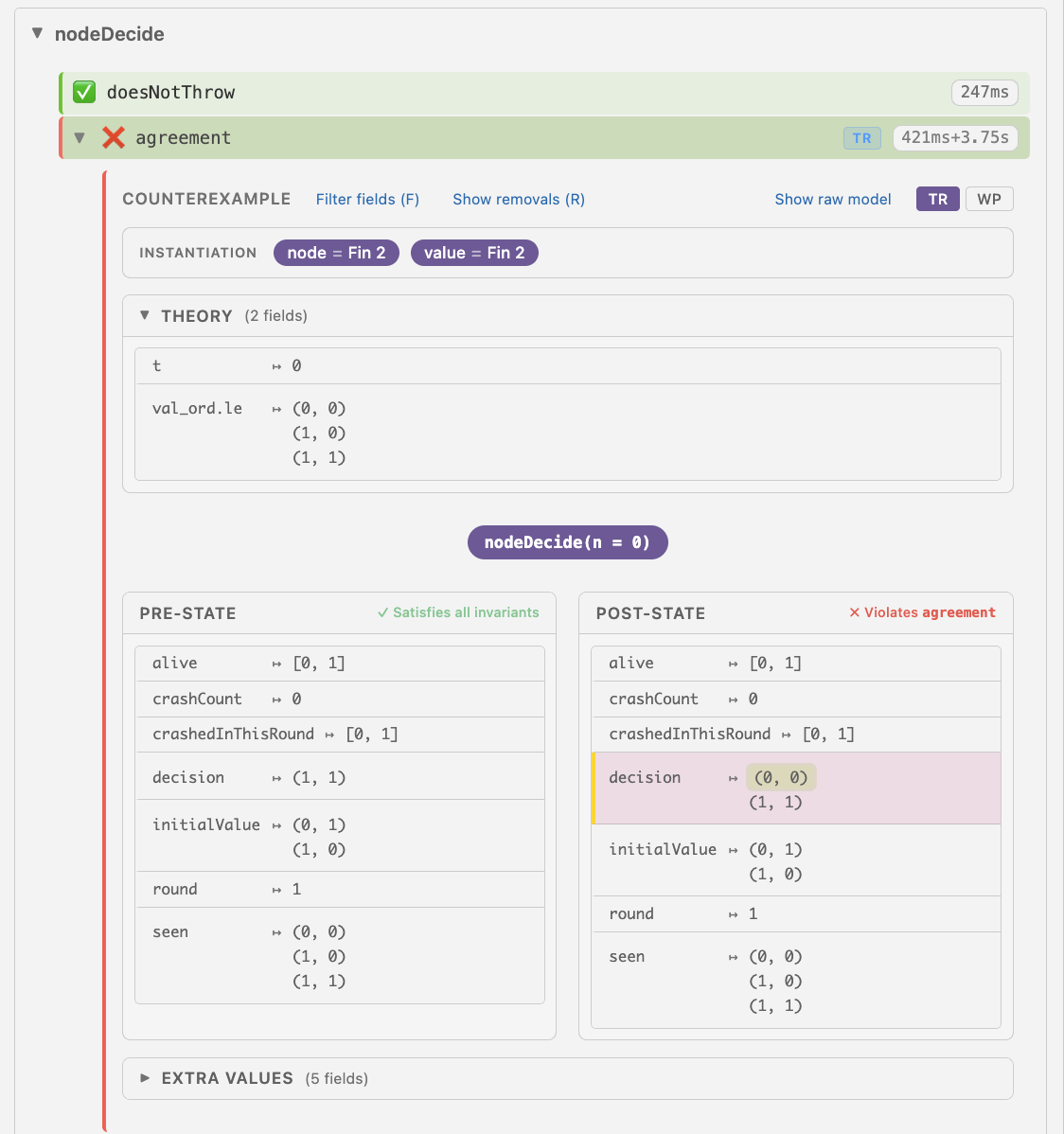

nodeDecide and re-run the model checker, Lace will show the following report:

In the state that violates the property, the relation decision stores two

pairs of values, namely, (0, 0) and (1, 1), meaning that the node 0

has chosen the value 0, and the node 1 has chosen 1, which clearly

violates the agreement property. Notice that the model checker not only reports

the violation of the agreement property—it also constructs a concrete

execution trace, demonstrating how a property-violating state can be reached

from an initial one.

In addition to discovering violations of safety properties (such as

agreement), a model checker can also be “tricked” into discovering

reachability bugs—scenarios in which a protocol does not do anything useful.

To see how to do that, let us uncomment the line assume ∀ w, seen n w → le v w

of nodeDecide and comment out the line decision n V := V == v. Clearly, now,

no node ever makes a decision, which means that both agreement and validity

always hold true, as the premises of their implications are always false. This

can be confirmed by re-running Lace, which reports no errors.

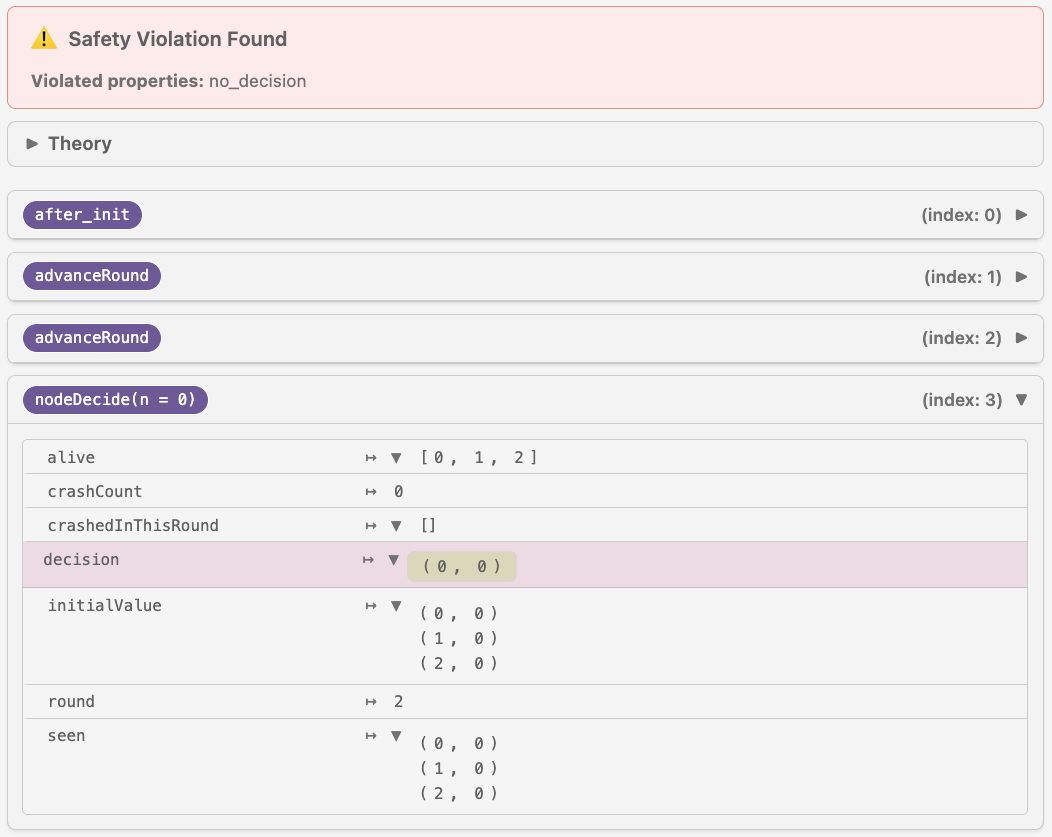

One can check whether the protocol does, in fact, reach “interesting” states by stating a property that we want to be violated, such as the following one:

safety [no_decision] ∀ n v, ¬decision n v

The property no_decision simply states that no node ever decides on any value.

This is clearly not what we want, so an execution of a well-functioning protocol

should have a state in which no_decision becomes false. However, if we rerun

the model checker on Floodset in its current form, no violations will be

reported. This means we’ve just discovered a reachability bug. By uncommenting

decision n V := V == v and reverting the protocol to its initial state, we

make it so that no_decision is now violated, which results in the following

report, demonstrating a trace that does lead to a node making a decision:

Formal Safety Proof and Inductive Invariants

So far, we have managed to check that no execution of our model of the Floodset

protocol violates the desired safety properties for some fixed values

of its parameters: node, value, and t. This gives some certainty that we

have got the protocol right, but it does not serve as a proof of this fact. What

we want to ensure is that no execution violates the safety properties for any

values of node, value, and t.

This statement can be phrased as a formal theorem, which can then be proven

by induction on the length of the execution. Specifically, we can derive that

the desired safety properties (e.g., agreement and validity) hold for any

state of the system if we prove the following two facts:

- These properties are true for any initial state, and

- If they hold true for a state

s, and a states'can be produced fromsby applying one of the protocol’s actions, then these properties also hold true fors'.

You can recognise part (1) as a base of a proof by induction, while (2) is the induction step. Veil provides a convenient way to assemble Lean theorems corresponding to the statements (1) and (2) for a specific protocol, out of the protocol’s description and its stated safety properties. We can then attempt to prove those properties automatically by typing the following command:

#check_invariants

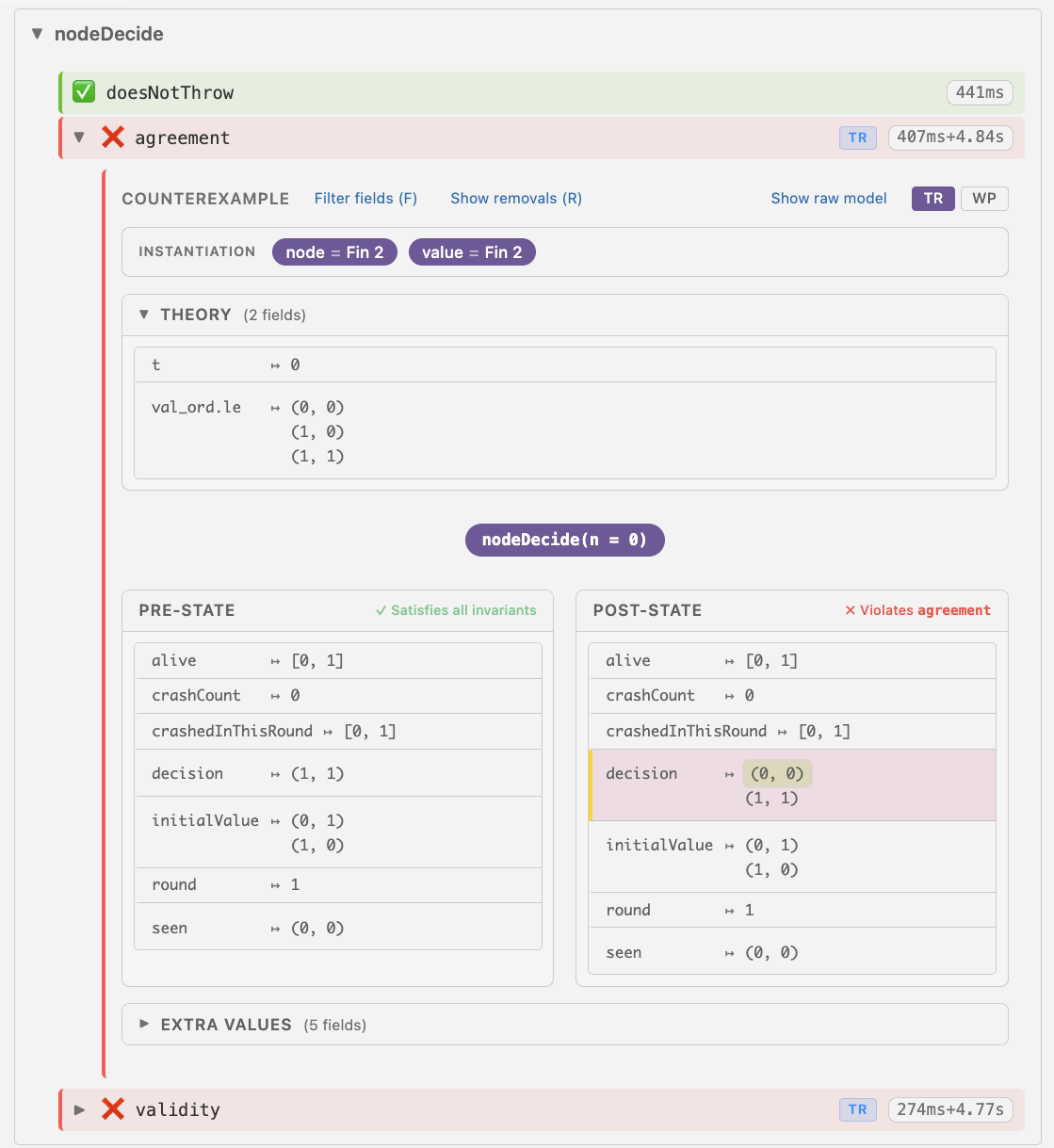

As a result, for this example, Veil generates 12 Lean theorems, out of which 10 are proven automatically, while two are disproven. Let’s take a closer look at the generated report shown in the Lean InfoView:

What it states is that for the action nodeDecide, it has discovered a pair of

states, a pre-state and a post-state, such that all the safety properties (also

sometimes called invariants) hold for the pre-state, but the post-state

violates agreement. This example refutes the statement of the induction step,

but does not necessarily mean that the properties don’t hold for any reachable

state of the protocol—after all, we had strong evidence for them being true

given by the model checker. So why does the proof not go through?

It turns out that the pre-state of the generated counterexample is, in fact, not

reachable in any of the concrete runs of the system. It is generated simply

because this is a state that satisfies both our properties, as required by the

premise of the induction step, which does not talk about actual state

reachability. Such spurious counterexamples, known as counterexamples to

induction (CTI), can be eliminated by stating more properties that we

believe hold true over the system. For instance, by examining the provided

counterexample, we can notice that, according to it, the node 1 has decided on

the value 1 (decision ↦ (1, 1)), even though it hasn’t “seen” it (the seen

relation only contains the pair (0, 0)). This is clearly not something that

could happen during a concrete execution, so we can add the corresponding

property to be included in our induction hypothesis:

invariant [seen_decision]

∀ n v, decision n v → seen n v

The property seen_decision states that any value that becomes some node’s decision must have been seen by this node. Sadly, running #check_invariants fails again, but now with a different CTI:

After looking at the counterexample, we can notice that the value of

crashCount in the pre-state is 0, while both nodes 0 and 1 are marked as

crashed in this round, and yet alive at the same time. Again, this is not

something that would happen after a valid run in the system. We can try to

eliminate this outcome by adding the following property to the set of invariants

we use in our proof by induction:

invariant [crashed_not_alive]

∀ n, crashedInThisRound n → ¬ alive n

And again, this generates another counterexample, different this time. What we are doing here is called inductive invariant inference, and, as we’ve discussed in the previous post, there is no algorithm guaranteed to always find a set of inductive invariants for a given initial set of properties to hold—even if they do hold.

Luckily, with a bit of understanding of how the protocol works and by analysing the counterexamples to induction produced by Veil, we can eventually provide a sufficient set of invariants for the system so that all generated theorems are proven, thus delivering the correctness proof for the protocol with regard to our initial properties. These invariants can be found in the Floodset implementation available on GitHub.

AI-Powered Inference of Inductive Invariants

I know you’ve been waiting for this part!

Indeed, the process of inferring inductive invariants manually is quite tedious, so having some automation here would go a long way. In the past, several academic efforts in the systems research community attempted to automate invariant inference by applying traditional symbolic enumerative techniques (examples of such frameworks are I4, SWISS, and DuoAI).

Nowadays, we have Claude Code, so we can just use it with the feedback in the

form of counterexamples provided by Veil. In fact, most of the auxiliary

invariants required to verify the agreement and validity of the accompanying

Floodset protocol

model

have been obtained by Claude Code automatically within just a couple of minutes

from a prompt “Infer the invariants necessary for #check_invariants to

succeed. Use counterexamples provided by the verifier.”

Concluding Remarks

There are quite a few aspects of Veil we haven’t discussed yet, but I hope to elaborate on them in future posts.

For example, even though Veil is just a Lean library, allowing any of its

theorems to be proven in Lean directly, we didn’t get to use Lean proof mode and

tactics in this tutorial. This is because we got quite lucky with our encoding

of Floodset, which allowed for its inductive proof to be obtained fully

automatically with the help of SMT solvers (Veil uses cvc5 as the default one),

invoked by #check_invariants under the hood. In one of the next posts in this

series, we will discuss protocol formalisations in Veil whose verification

requires a combination of interactive and automated proofs in Lean.

If you are interested in learning more about Veil’s capabilities as a verifier, you should check out this CAV’25 paper. You can also find some takeaways from implementing Veil on top of Lean in this paper presented at the recent Dafny workshop.

Even though Claude Code was incredibly effective at inferring inductive invariants for proving correctness of a protocol, it was not as reliable as a mechanism for protocol auto-formalisation. This is not due to it getting Veil’s syntax wrong: contrary to my expectations, it managed to guess the meaning of all its unusual syntactic constructions correctly, or quickly corrected all its mistakes with the help of the compiler errors. The main problem is that the protocol definitions it produced in Veil were missing crucial parts, making them vacuously correct but also useless. For example, one of the first versions it produced modelled all crashes in the same action as the broadcast without accounting for partial message delivery, so the resulting protocol would reach agreement immediately after the first round. Issues like these were discovered with multiple runs of Lace to test reachability properties—as discussed above.

Furthermore, Claude Code was prone to overcomplicate things, for instance, by introducing state components that were not necessary for modelling the essence of the protocol, such as a relation representing in-flight messages.

While these shortcomings might be eliminated in future models, my experience so far still demonstrates that the presence of the human expert is crucial for getting a faithful and concise formal specification of a system at the right level of abstraction.

Acknowledgements

I’m grateful to Seth Gilbert who suggested taking a look at the FloodSet consensus protocol as a case study for Veil, and to George Pîrlea and Qiyuan Zhao for their comments on this post.

-

TLA+ comes with TLAPS (TLA+ Proof System) for writing deductive proofs in a bespoke tactic language, but it’s a separate tool. To the best of our knowledge, it’s not commonly used (although, if you are using it, please get in touch with us—we are curious to learn about your proofs!). It is also not as expressive as modern proof assistants, such as Rocq or Lean. Quint allows for a form of automated correctness proof that is not guaranteed to always succeed, even for correct protocols, due to the limitations of its underlying solvers. ↩

-

Other famous consensus protocols, such as Paxos or Raft, do not assume synchrony and work under a weaker assumption of asynchronous communication, where one cannot tell the difference between a slow and a “dead” participant, as the messages can take arbitrarily long to deliver. That is, they guarantee correctness without any timing assumptions, but, in practice, they also rely on time-outs to make progress. ↩

-

For those who think in terms of Lean (or Haskell), the

instantiatecommand simply imposes theTotalOrdertype class constraint on the elements of the abstract typevalue. ↩ -

This notation is inspired by the syntax of the Ivy verifier for distributed protocols. ↩

-

Veil syntax

let x :| p xallows one to constrain the values of a randomly pickedxto only those that satisfy the Boolean predicatep. This operator, known as Hilbert’s epsilon operator, is very convenient for modelling constrained non-deterministic choice. ↩

Comments